Philippe Garrel's Cinema of Secrets | Vague Visages

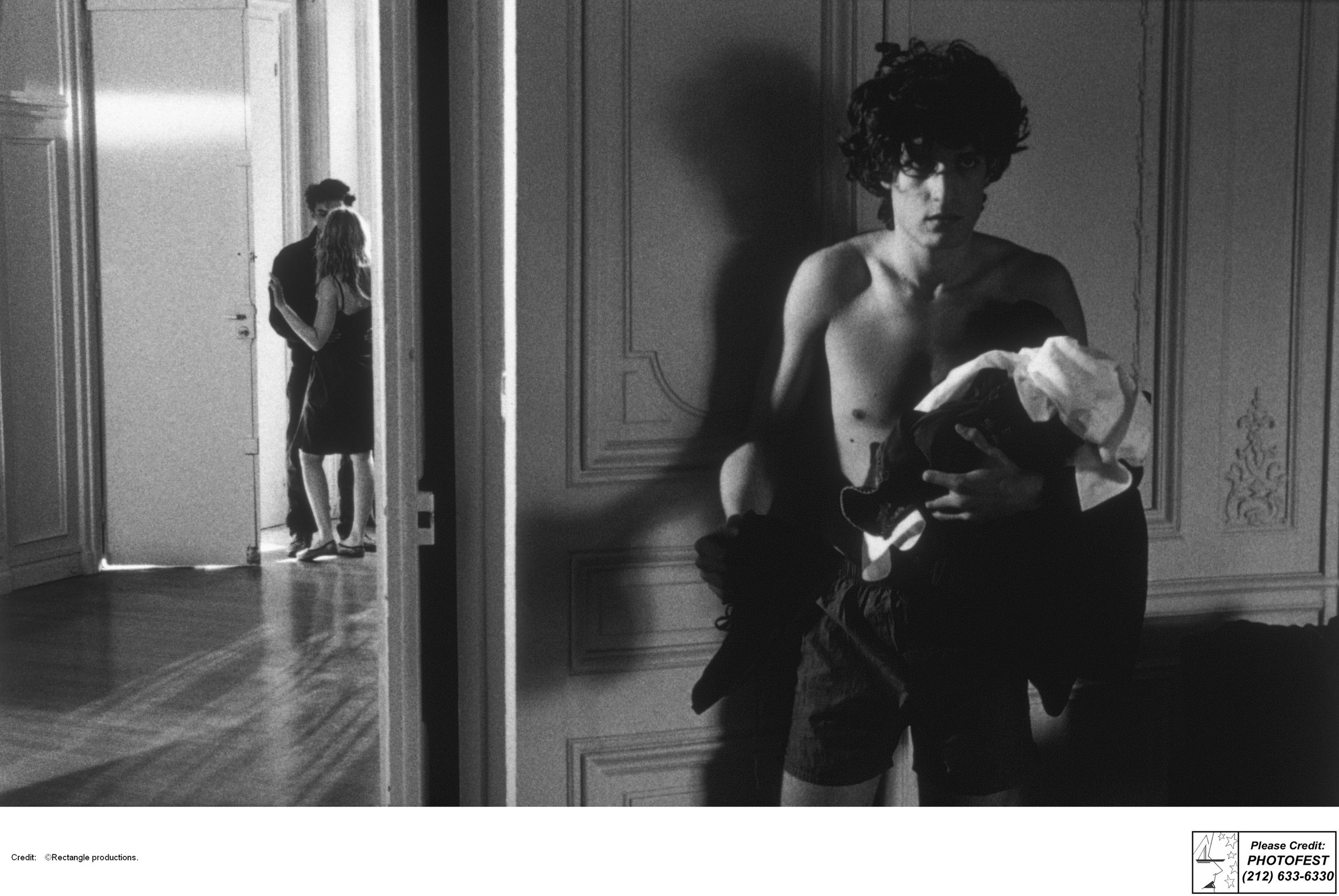

LOUISE CHEVILLOTTE AND ESTHER GARREL IN LOVER FOR A DAY.

by Julia Bozzone

“Cinema is Freud plus Lumière,” the French filmmaker Philippe Garrel once said. This succinct equation is an apt description of his work, with its arresting close-ups of faces and the direct, expressive outpourings of his actors, framed in luminous and painterly compositions. “I’ve produced whole screenplays by cobbling together dreams,” the director has said, calling the ambiguous images a source of inspiration because “a dream is indisputable.” Garrel’s personal films — which chronicle the rhapsodies of love and, much more frequently, its torments — are visually stunning and spiritually potent, embedded, as they are, with his interest in “words, faces, dreams, sexuality.” His movies explore the psyche of lovers in a focused and intense way. In fact, his exquisite studies of romantic turmoil might well make Garrel, 69, the most underrated director working today.

Garrel is probably best known for his relationship with the German musician and model Nico and for being the father of the dashing actor Louis Garrel, but he’s also a masterful auteur who makes piercing, powerful films — like The Birth of Love (1993), Regular Lovers (2005) and Jealousy (2013) — that are intimate, nuanced and devastating studies of interpersonal dynamics that often play out in bedrooms and cafes. As stereotypically French as that sounds, his movies are effective and penetrating, and distinguished by their poetic sensibility. “It is almost uncanny how well you feel you know these people, even as their motives and behavior remain opaque to one another,” critic A.O. Scott wrote in his review of Jealousy for The New York Times.

After seeing Le petit soldat (1963) by the French New Wave director Jean-Luc Godard, Garrel was electrified and inspired to make his first film at age 16. Starting in 1969, he had a tempestuous, 10-year-long relationship with Nico, who starred in many of his films and has arguably served as his greatest muse. This fall, the Lower East Side movie theater Metrograph is hosting the biggest U.S. retrospective of Garrel’s lucid, startling and elemental oevre. While he started out making experimental, marginal works (shown in the recently completed first part of the film series), Garrel has specialized in movies with minimal narratives since his 1979 film The Secret Child, usually featuring love triangles and often shot in a stunning black and white. His son Louis frequently stars in his newer work.

During our conversation, Garrel was personable, generous, and pragmatic — that is to say, just the opposite of what you might expect from an artist who is known for his heart-wrenching masterpieces about searching, anguished people like I Can No Longer Hear the Guitar (1991) and Emergency Kisses (1989). Both Garrel and his clear-eyed new movie, Lover for a Day, have a lightness of spirit that is totally unexpected, and here’s something else that you didn’t see coming — it’s a comedy. (Moments after we spoke, Garrel’s closing remarks while introducing his haunting silent 1968 film, Le révélateur, made when he was just 20, were also lighthearted: “It’s not the greatest, but here it is.”)

The night before, after the New York Film Festival premiere of Lover for a Day, Garrel explained that he usually refrains from doing press events, not for snobbish reasons but simply because he enjoys making movies and prefers to focus on filmmaking itself. Speaking to the Film Society of Lincoln Center programmer Florence Almozini, he outlined the basics of his current filmmaking process. For about a year, he rehearses with actors once a week, developing the story and the script. He mentioned how essential the rehearsal process is — and how much he values good acting — and noted that Alfred Hitchcock once commented that he found it was necessary to rehearse a lot more after transitioning from silent films to talkies. (A number of Garrel’s most notable early films were silent.) The screenplays of Garrel’s films have been much more carefully worked out in recent years. He shoots his movies in sequence, with only one take per scene, making each film quickly.

Also unexpected was Garrel’s newfound commitment to feminism and his disclosure that women have embraced his recent work. As an artist, Garrel has long been unafraid to examine the shortcomings of men as fathers, husbands, and boyfriends, and the men in Garrel’s films often behave badly. For his recent films, the input of his screenwriting collaborators has been critical. His new film, the third part of a sort of trilogy, stars his daughter Esther as a young woman who returns home to find out that her father’s new girlfriend is her own age. “We met together frequently,” Garrel said of his three Lover for a Day co-writers, which include his wife. “I think it was important that [we were] a combination of men and women. We would discuss potentially misogynist elements and I think that’s crucial in making these films.” In the past, he acknowledged, “female roles of this kind were written by men, and I think that that’s fairly archaic.” Here, though, the dialogue between Esther’s character and her father’s girlfriend was written by women, which helps to explain why the female point-of-view is so authentic and precise, and why the way the young women talk amongst themselves seems absolutely real.

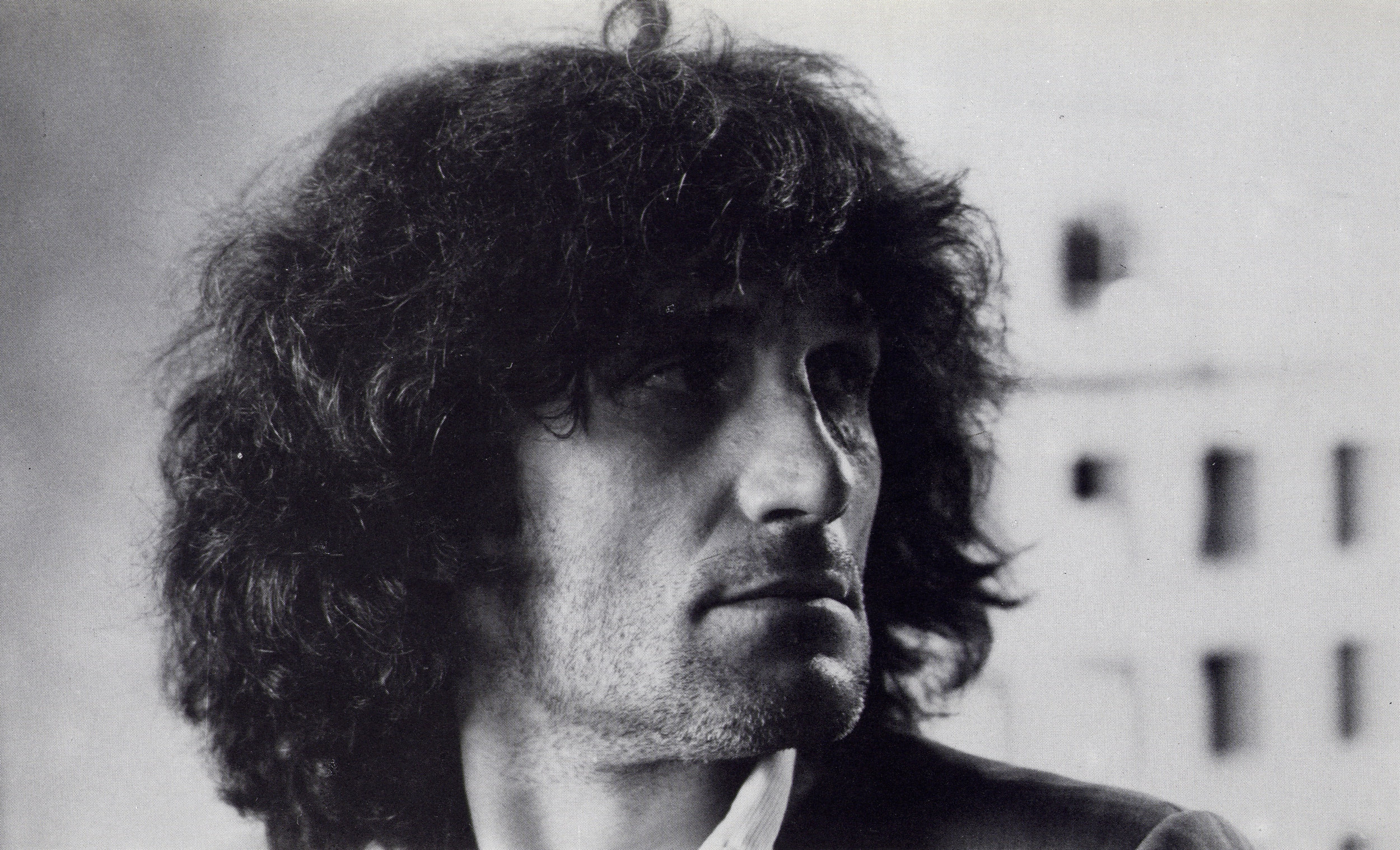

DIRECTOR PHILIPPE GARREL IN HIS 1989 FILM EMERGENCY KISSES. COURTESY OF THE FILM DESK/METROGRAPH.

Though he is revered as an important artist in Europe, Garrel is hardly known by anyone outside of cinephiles in the States. Surrounded by gawkers after the movie’s premiere, Garrel seemed faintly amazed.

The second part of Metrograph’s series devoted to Garrel’s narrative films opens on Friday, November 17. His new film Lover for a Day will open theatrically in New York on January 12, 2018, exclusively at the Film Society of Lincoln Center. Dominique Borel translated our conversation.

JULIA BOZZONE: Can you tell me a little about your inspiration for making this movie?

PHILIPPE GARREL: The Shadow of Women, the film that preceded Lover for a Day, did better than any of my others movies had. Once you’ve had a success like that, you’re given the room to move forward and do something else. Of course, financially, I could have done a movie with a bigger budget. If you work within the star system and cast a star — like I’ve worked with Catherine Deneuve — it brings in roughly double of a movie that’s not through the star system.

So, I said to myself, if I propose doing another movie for the same budget as Shadow of Women, which is half of what they would have given me, and I suggest that my daughter plays the lead, they’re not going to turn me down. And what I’ve done with my children is I don’t want to suffocate them, so I let them get a few movies under their belts before I work with them. I did that with Louis — he had worked on a few movies with other filmmakers — and the same was true with Esther as well. And the timing was right. She had a few movies under her belt, and that was actually when I wanted to use her.

BOZZONE: Your movies are almost always concerned with romantic love, but they’re also very concerned with the family unit and family dynamics. Do you work with your family members in part to try to understand their perspective?

GARREL: I don’t really think so because it’s like [filmmaker] Leos Carax said, “Cinema destroys life.” For instance, when I was working with my daughter, she really had to be good because people have an eagle eye on it. If she had been bad, it could have been extremely, extremely destructive in terms of the whole process. It’s the opposite, I think, of working out family issues. You’re really taking a leap of faith in terms of it working because it’s much more dangerous.

There was a film from Wim Wenders, Until the End of the World [1991]. He shot it with the woman he was in love with at the time. A critic wrote of her, “Move your ass. There might be a Wim Wenders film behind you.” Imagine her coming home with that paper and showing it to him! It doesn’t do anything to bolster the couple. If anything, it brings them down, so that’s where moviemaking can be destructive in terms of family connections or love connections.

If they had written after this film, “Well, Philippe did his work, but his daughter was a disaster,” then I’d be in for 10 years of problems with my daughter, not the opposite. But I’m not sure that was the nature of your question.

BOZZONE: With Jealousy, it seems like you were trying to understand an experience your father went through. Emergency Kisses focuses on your then-wife’s perspective. Lover for a Day is again from the female perspective. Do you sometimes make a movie in hopes of better understanding another person’s point of view?

GARREL: I see Jealousy as about neurosis in women.

BOZZONE: Yes — even though the basic storyline is something that happened to your dad.

GARREL: Shadow of Women was about libido in women.

BOZZONE: Last night, you suggested Jealousy was exploring neurosis in women like Michelangelo Antonioni’s Red Desert (1964) did.

GARREL: You can see in the Antonioni film that neurosis is what prevents her [Monica Vitti’s character Giuliana] from living normally. What’s different, what I would say is newer, is to have gotten through machismo and now be interested in women’s issues.

BOZZONE: You personally?

GARREL: Yes. Like Jean Rouch from the New Wave, for example, consciously defended black people. It’s similar in the fact that consciously I’m creating work to stand up for women. The fact that my movies are more successful now than they were 20 or 30 years ago, a lot of it is attributable to women having responded positively to the movies. There’s a female fan base.

BOZZONE: That’s interesting. I enjoyed this movie and could really relate to it. I do love movies of yours like The Birth of Love.

GARREL: That’s men going off-course — this is women.

BOZZONE: Your method of directing actors is based on “unblocking” them or freeing them. What made you think you could do that?

GARREL: You know, I really don’t know. When I was 15, I was hesitating between being a painter or a filmmaker. I knew I didn’t want to be an actor like my father, but I had the feeling that I could get actors to say something — that I could have a hand in that — in terms of allowing actors and maybe unconsciously guiding them to where they needed to go. And I knew it was an industry where you had to procure money for the projects, and for whatever reason, don’t ask me why, I thought, okay, that’s something I can do.

That’s what called having a vocation — you know, we think we can do it, and because we think we can do it, we believe we can do it, we can do it.

BOZZONE: You started out as a painter. What is your relationship with your cinematographer on any given movie?

GARREL: Well, there’s another thing. I felt that being a painter was an extremely solitary existence, and I liked the idea of teamwork.

I’ll tell you one of the ways that I work with them. On Jealousy, I worked with Willy Kurant — he’s now too elderly to work, but he was a big DP [director of photography] for the New Wave — and I said to him, “I want it to look like a charcoal drawing,” whereas for Lover for a Day, I told the DP, “I’d like it to be a pencil no. 2 drawing.” And then when I worked with the DP in color on A Burning Hot Summer [2011], I said, “I do not want an oil painting, I want it to be a watercolor wash.” Cinematographers are so image-conscious that they can understand that kind of language. They can translate it.

You’ll find on almost any set the DP will come to the director and they will say, “Look at this painting. You should really think about this.” And they usually show an Edward Hopper painting. It makes them think of movies, because he had almost a cinematic painting style. In fact, you can put your hand in the fire when you go on a movie set that, at some point, the DP is going to come forward with a photograph of an Edward Hopper painting. So I say to my DP, “I don’t want to see Edward Hopper, okay?”

It’s unconscious and collective behavior. If you do a black and white movie and you start to have a conversation with your DP, they’re going to start to talk about photographs and important photographers, like [Henri] Cartier-Bresson. If you’re doing a color movie, for some reason, the dialogue turns to painting: “Have you seen this painting or that painting?” That, I think, might be a mistake because trying to live up to [Leonardo] da Vinci is not the same as living up to Cartier-Bresson. We never rely on great photographers for color films because I don’t believe that there really are great color photographers.

It’s interesting, this question, of how you come to have an image in black and white or in color in terms of what’s in the past. It’s an ongoing sort of process.

BOZZONE: In your recent black-and-white movies, the characters live in apartments that are unadorned, the women wear virtually no makeup, and the streets are usually empty. Why?

GARREL: The streets are empty because if you’re in a street that isn’t, you can’t hear anything because I’m doing direct sound. Why aren’t they wearing makeup? They’re not any more beautiful with makeup than without it. In black and white, you don’t have to wear makeup, whereas if I was shooting in color, because of the color of the skin, you have to put on makeup in order for it to read correctly. And it’s to your advantage not to have 45 minutes of makeup going on before the takes, if you’re shooting a movie in 21 days.

BOZZONE: You’ve said that an artist doesn’t improve. He goes through stages, and he can remain faithful to himself or not. What is your perspective on age? Do you feel the same inside as you always have? Do you feel wiser?

GARREL: I don’t think the films I’m doing today are better than the films I did 50 years ago. It’s hard to determine why certain artworks become totems, or become considered great art, and others become taboo. The audience is either going to be open to what you’re showing them and they’re going to take it in or they just cut you off. And it’s a big mystery why that happens. It’s like fashion. Things that are in fashion, little by little, they grow on you and you like them and you think they’re fantastic, and then all of the sudden, it’s out of fashion, and you think it’s ugly and you don’t like it anymore. Consciously, we know that it’s us, it’s the way we see it, it’s what we experience — it has nothing to do with whether it’s really good or bad. It’s just your experience changes.

How you become fashionable as an artist is a big mystery. It’s what every artist wants, but how it happens is another story. I don’t think it’s necessarily because there’s been an evolution or progress.

BOZZONE: But do you feel wiser with age?

GARREL: The one difference is that when I was younger and I’d finish a film, I’d suffer for months, thinking about all the mistakes that I made in that film. Now that doesn’t happen. I don’t think about that, and I don’t suffer when I complete a film.

BOZZONE: You’ve talked about making movies that draw from life without giving away other people’s secrets. How do you do that?

GARREL: Well, there’s an ethical question involved. You don’t want to hurt those that you took from in real life.

BOZZONE: Right, but it seems that your movies express the essence of specific relationships. As a viewer, you feel like you’re in on a secret. How do you create that sense of intimacy, always?

GARREL: When you write the screenplay, you have to specifically refer to things you’re ashamed of in your own life, not the things that you’re proud of. Then the audience is going to recognize things that they’re ashamed of in themselves, and they’re going to feel connected with it. That’s why you feel like you’re understanding a secret — because it taps into your own secrets.

November 16, 2017

Editor: Q.V. Hough

An expanded version of this piece was originally published on vaguevisages.com.